Blog

Music production tips and advice: separating myth from fact

26 Sep '2019

Producers and engineers are a strange breed of person. The world of production is full of superstition, voodoo and old engineer’s tales, and despite technology moving on, these continue to circulate in the 21st century.

It often seems that the world of audio is a lot like the world of wine – nobody quite knows what’s true.

Trust Your Ears… and Nothing Else

Today’s producers have access to fancy equipment and software, and some of the most sophisticated visual analyzer plugins to have ever been conceived. Shiny synths make you feel like they sound great just by how awesome they look, and AI assistant plugins offer to guide us in making crucial mix decisions. With all this eye candy in the studio, should we completely ignore it and solely trust our hearing?

IS IT TRUE?

Yes but no. Trusting your ears is certainly still your most valuable strategy, and if you could only pick one sense to use to evaluate your music production, your hearing would obviously be it. But there’s so much more to look at that can provide an insight that’s unavailable elsewhere.

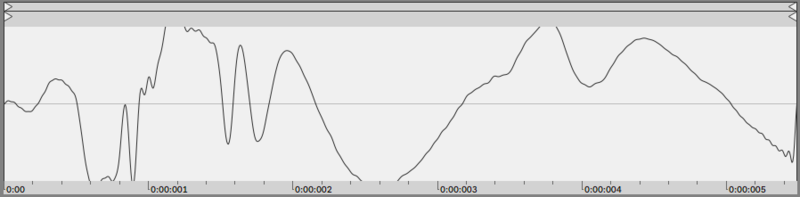

Visual analyzers, for example, can give a crucial insight into the frequency balance of a track. Maybe there’s inaudible low-end energy that needs to be high-passed out that isn’t coming through on your playback system. Perhaps there are frequency spikes in one area of the spectrum caused by a sound you intended to have for sonic energy elsewhere.

Human hearing is subject to changes: there’s ear fatigue, Fletcher-Munson equal-loudness curves, and even the variability of where our head’s placed in the room. Having visual cues that don’t change over time can give you a super-reliable method of checking your sound, as long as you don’t lean on them too heavily.

Egg Boxes on the Studio Walls

It’s an old cliche of the home studio: walls lined with egg boxes in an attempt to improve the acoustics of a room. But do egg boxes on the wall really help in music studios?

IS IT TRUE?

No. Egg boxes probably don’t work well as sound diffusers, and they’re basically useless at isolating (ie stopping) sound.

Perhaps the misconception comes from the regular, dipped shape of good acoustic foam. These foam panels do certainly look like they’d hold a bunch of eggs if placed on your backs, but they’re actually meant to go on walls.

The mythology seems even more ridiculous when you realise that acoustic foam isn’t really designed to stop all sound – it’s designed to be placed strategically in order to absorb it in crucial places in a control room rather than to completely and fully destroy all sound energy.

You Need to Record in a Great Room

It’s 2019, bedroom production is the norm, but the world of professional recording studios still exists. Is it worth spending money on the perfect recording space now that we have advanced technology to fix the problems in less-than-great takes?

IS IT TRUE?

Yes, if you want the best recording, a well-treated room is necessary, but for single vocal performances, it’s possible to do a lot to make your current room better.

These days we have software like iZotope RX, Accusonus’ ERA Bundle, Acon Digital’s Restoration Suite, and more that offers to fix bad recordings. These suites can take away noise, electrical hum, even reverb, clicks, pops, plosives and mouth clicks to get you the ultimate audio experience… so what’s the point in even having a decent space to record in the first place?

Short-term, the crucial thing to bear in mind here is the time and money it takes to get the right sound. It’s your own calculation as to whether you prefer to spend money on a good room or money and time on using restoration software.

But in the long run, there’s a lot to understand about recording in a good space. Learning to record is a part of learning to produce in general, and learning how sound works in a room is crucial to learning how mixing, mastering and sound design work. Good-sounding, professional, and characterful recording rooms have their sound for a reason, and often, having something recorded in a room like this is enough to give it a sense of space and location in a mix.

Then again, it’s very possible to improve the sound of a bad room. Check out our advice on monitor positioning or Home Recording Tips to learn more about upgrading your sound from home.

It’s not OK to Mix on Headphones

Despite being the cheapest, most convenient option for producers to play back their DAW projects on, headphones are looked at with some scorn by many producers, who feel that ‘proper’ monitor speakers are the only serious way to mix.

IS IT TRUE?

Yes and No: It’s not OK to rely on any one playback method thing for mixing, whether that’s just using monitors or just using headphones. Mixing requires a number of playback systems to properly judge quality, and headphones should be an integral part of your referencing process.

When well placed and at work within a well-treated room, monitor speakers give a more faithful representation of both stereo field and frequency balance than headphones do. Nevertheless, when you’re working in less-than-ideal conditions, the frequency imbalances caused can make monitors just as unreliable as headphones. In this situation, headphones are a very good candidate for mixing duties, and don’t suffer from monitoring problems like the need to sit in the sweet spot between the two.

What really matters is what you’re used to. If you know a system inside out, and have psychologically ‘calibrated’ yourself to it over weeks or months of listening to music you know well through that system, you’re in a very good position to judge the overall sound.

Whatever the winner in your quest to find your perfect system for sound design and workaday production tasks, the most crucial principle of mixing sheds some light on the issue: you need to listen to your work on multiple systems to truly understand how it sounds. Monitors, professional headphones, consumer headphones, car sound systems, bluetooth speakers, phone speakers and any other playback systems that you can access play a key role in this process.

Check out our article on the pros and cons of mixing on headphones here.

Less is More

It’s a saying so common that it’s become a trope, but is this piece of music production advice still relevant? Will making your music simpler give you a better chance of success?

IS IT TRUE?

Yes, it’s a fundamental law of making great music for the masses, but that doesn’t mean no one wants to listen to complex and intelligent music.

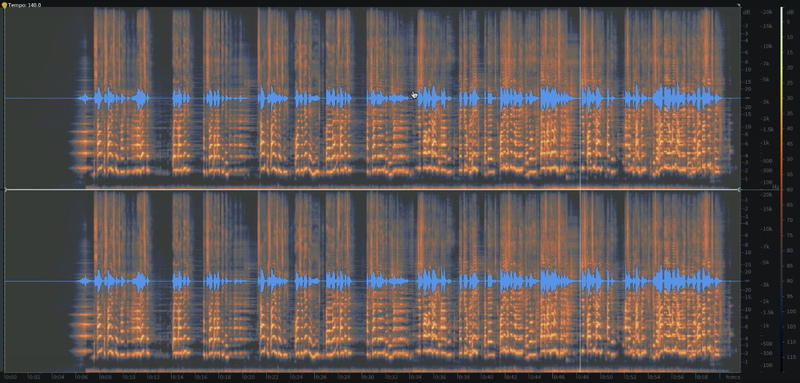

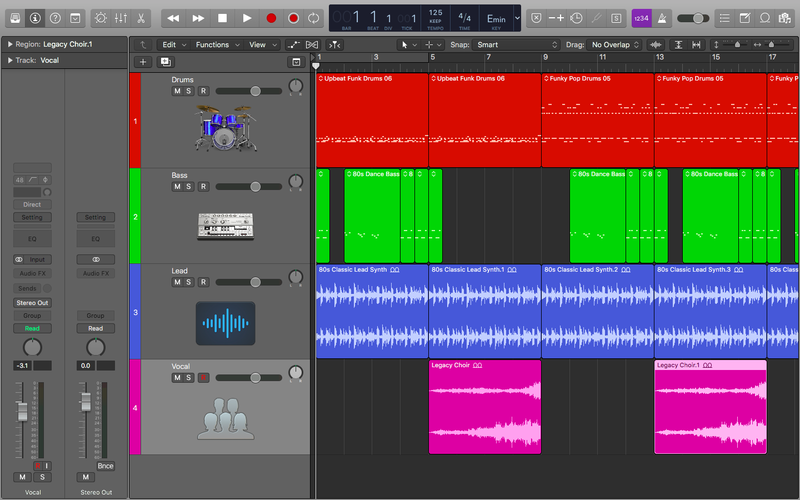

Back in the 00s, most DAWs still had a limited number of tracks, thanks to the low processing power of the day’s computers. In contrast, today’s DAWs can handle practically unlimited track counts, plugins, samples and instruments. So why not throw as much of it onto the canvas as you possibly can?

Sure, layering two sounds together to get the perfect snare, or creating variations on a synth patch in the left and right channels can be great ideas, and we’re not saying that you shouldn’t do these; but the essence of a good piece of music – the thing that makes it live and breathe – is simplicity. Remember to prioritise only a few focal-point elements, and keep everything else only if it’s really adding something to the tune.

When we get wrapped up in the technicalities, we lose sight of what’s actually important when making music: the end product. While you might see in-studio videos with producers showing off their massive multitrack projects, musically speaking, many of the most popular tunes in the charts will employ only three crucial elements to make them – the rest is just gravy.

That being said, there’s certainly a listener base for those wishing to make music using complex DAW projects, and a key group of people who would search out this kind of music? Other Producers.

While the secret to creating hits lies in keeping it simple – production is a reduction – there are plenty of people who actively go looking for something to stimulate their eardrums.

Only Make Cuts on an EQ

The old guard of music production was taught that the best results come from purely subtractive EQ – that where possible, you should only make cuts and refrain from boosting.

IS IT TRUE?

No. Hardware systems used to mean that engineers had to strive to keep noise to a minimum through a complex signal path. Digital systems don’t suffer from the same problems.

Back in the days when analogue tape fed a mixing console, and every studio effects processor was connected into that, every single piece of equipment in the signal chain would introduce its own noise floor. The tiny, inaudible amount of electrical and thermal noise introduced by a single piece tended not to matter, but the amount created by multiple pieces could really add up and become a problem.

For that reason, using EQs to cut rather than to boost became best practice. With cuts only, that electrical noise from other parts of the signal chain was only ever reduced, and boosts were reserved for the amplifiers built to do this as cleanly as possible.

But today’s digital processors don’t suffer from the same noise floor problems. Boosting a new sound with EQ won’t cause any problems, no matter how many plugins you’ve got on a chain – unless any of those plugins specifically aim to emulate the noise floors of analogue hardware. If you want to take your EQ abilities to the next level then read our top EQ tips.

You Can’t Polish a Turd

The crucial piece of sound engineering passed down from generation to generation still holds true: if you start with rubbish, you’ll end up with rubbish.

IS IT TRUE?

No, you can polish a turd… it’ll just take ages.

In practical terms, this means that you shouldn’t move onto mixing a track if the sounds (recorded or synthesized) aren’t good enough; and you shouldn’t send a track that isn’t well mixed onto a mastering engineer. In other words, you can’t fix it in the mix, and that’s not your fault!

With today’s insanely sophisticated software, you could argue that the old turdy adage isn’t nearly as true as it once was… but at the end of the day, its attitude is still very correct: if you’re not working with something great from the start, you certainly can’t be expected to turn it into anything better.

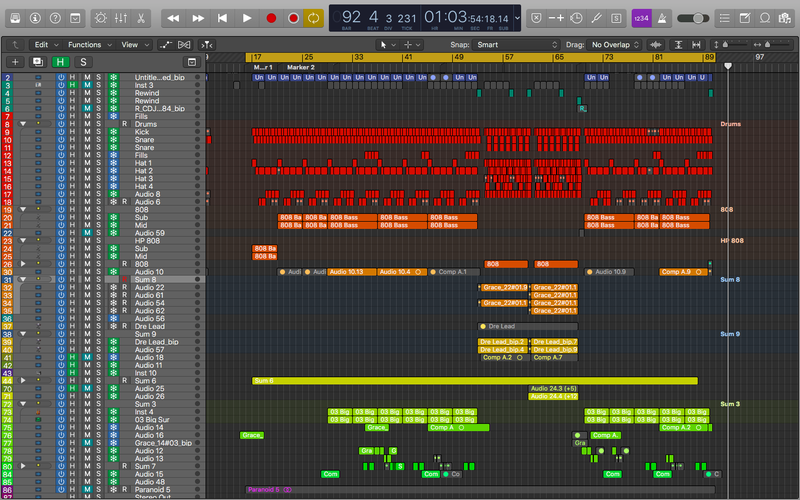

Don’t Clip the Master

It’s one of the first things we learn about recording, and then one of the first things we learn about exporting mixed or mastered audio. If the physics behind the waveforms is correct, data is lost when you overload a digital system by going over its ceiling of operation.

IS IT TRUE?

Not exactly. You’ll lose data in recorded sound, so be careful not to clip at this stage; but, clipping slightly at the master can sometimes be a useful strategy for loudness, depending on how it’s done.

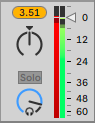

First of all, clipping inside your DAW’s mixer channels isn’t of consequence thanks to floating-point processing. The place you should traditionally be worried about clipping is when exporting from your master channels: when your audio is leaving your DAW.

When your DAW’s master meters go into the red due to clipping, you’re right to be cautious and bring things back down again. In the digital world, you can lose information from a sound if the waveform goes above the limit of the system’s capabilities. But load up a professionally mastered tune ripped from a CD at 16-bit resolution, and you’ll often see just that: clipping. Sometimes lots of it.

When a waveform goes above zero, into positive territory, your digital-to-analogue converter (DAC) applies a positive voltage to the loudspeaker. When the waveform goes below zero, vice versa. The waveforms you see in an audio signal (up and down) are analogous to the voltage applied to move a speaker (forward and back).

A speaker is a moving mechanical system with inertia, and so when a digital waveform approaches its limit and clips for two samples, the speaker won’t simply stop at the first clipped sample – it’ll go past it, then fall back through the second clipped sampled, recreating the waveform over the digital ceiling. A slight clip can actually help you get some more headroom out of your system.

And then, when clipping for a number of samples only, can the distortion introduced even be heard? That’s debatable, but as long as your tune isn’t clipping constantly, perhaps you have less of a problem than you think.

The final point of the argument is that clipping is possible to get away with, at the expense of loudness. Remember, though, that distribution systems you upload to will check your waveforms and often bring down the entire volume of your track to compensate for any forced loudness. Clipping’s not simple – it’s a balance that each person needs to strike on their own.

High-Pass Everything

One piece of advice back in the olden days of music production was to high-pass every element of your track – even sometimes the kick and the bass – for a better, cleaner overall result.

IS IT TRUE?

No. And it can actually make things worse if you do.

This was indeed a good idea in the days of recording, analogue equipment and vinyl records, but today is doesn’t hold as true. One reason for this advice was recorded instruments. When recording actual air in an actual room with an actual microphone, movements within the room are more likely to cause low bass rumble. Fortunately, these days we can view whether or not recorded rumble exists or not using a spectrum analyser. A look at totally synthesized sounds most often shows absolutely no energy down in the lowest ranges.

If there’s no rumble on the very lowest end, you could actually be hurting things by high-passing. A high-pass filter tends to cause phase delay in the signal you’re sending through it. While this is often a worthy trade-off when there’s rumble on other channels, when there’s no rumble to cut, you’re only hurting your final result.

However, as discussed on Loop+, high-passing can be used to reduce muddiness in a pinch.

Sound Design, Arrangement, Mixing and Mastering are Separate Stages

Over the years, with music production becoming a computer-based activity, the way people make music had changed to fit the unlimited possibilities available. But many still advise keeping your sound design, arrangement, mixing and mastering processes as discrete stages of the production process.

IS IT TRUE?

It’s up to you. If you work better this way, it can provide you with a structured way of doing things that you can benefit from… but you should try it both ways in case you like mangling it all together.

As the DAW became a place where people could design, arrange, mix and master a tune all in one project, people naturally started to gravitate towards doing it that way. The advantage of this is that you can take every stage with every other stage in mind.

Is the bass sound you’re making going to clash with the sound of the keys you already have? No need to wait for the mix to try and force the two together – you can fix things right at the start in your sound-design session. And if during mixing, you need to make a change to the layering of parts or to the MIDI notes involved, that’s also still possible.

But the theory goes that splitting all four into separate stages can be better for your work. By having sessions reserved for individual tasks, you’ll perform better on each one, keeping your mind focused on which task is at hand at any given moment, and doing better at it. This method also helps you to commit and move on – being able to tweak your synth notes at the mastering stage might be possible, but that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to go back and make that ‘one last tweak’.

In reality, what matters is which method works for you. Which way of working helps you to do your best work, your quickest work, and of course, to finish the new material fastest.

Want some Ableton sound design advice? We’ve got you covered.

You Need to Learn Music Theory

Studying your craft is the most important way to become better at it, right? And so if you’re learning music, you should spend your time learning the rules in order to use them properly.

IS IT TRUE?

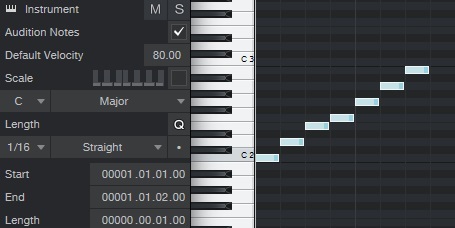

No. Music theory can be a useful thing to learn, and can provide you with some creative ideas, but the number of famous musicians who know nothing of it can shock you once you start exploring.

It’s one of the most divisive parts of making music, and everyone seems to have an opinion. Theory isn’t a means to an end. It doesn’t make the wheels go around – it just explains why the wheels go around. Just as you can learn perfect English from birth without knowing what the past participle tense is, you can express yourself musically just by ear. Theory often helps to lend a name to things, and to explain why they work after the fact, but it isn’t instrumental in making those things happen in the first place.

Then again, music theory can be a good source of ideas. Perhaps you’re stuck at a certain point in a tune and want to make things happen. Flicking through a theory book for ideas and inspiration is a valid way to move forward. See which chord extensions work and how to invert them. Try out a Neapolitan Sixth. Even if you don’t end up employing the ‘perfect’ practice to the theory you’ve just learnt, you’ve been pushed in a certain direction and have found something new, courtesy of those stuffy books and dusty chalkboards.