Blog

8 Ideas to Shake up your Chord Progressions

28 Jun '2024

Got the same chords as everyone else? Here are 8 Ideas to make them truly yours.

Chord progressions are one of those annoying parts of music. Some of musical history’s greatest songs actually use very basic progressions, which is alright for them – but just using “the same old thing that’s worked a hundred times since the 1950s” is still a way to end up with music that goes unnoticed. Where do you find the balance?

In this article, we’re going to inspire you to take a sequence of chords and convert it into something better – something more unique. We’re not going to overhaul your progressions until they’re mostly punctuation marks and numbers, but we’ll offer some suggestions to make subtle tweaks to help it all stop your chord progressions from sounding like everyone else’s (or like you got them from a MIDI pack).

1. Use chord extensions

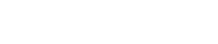

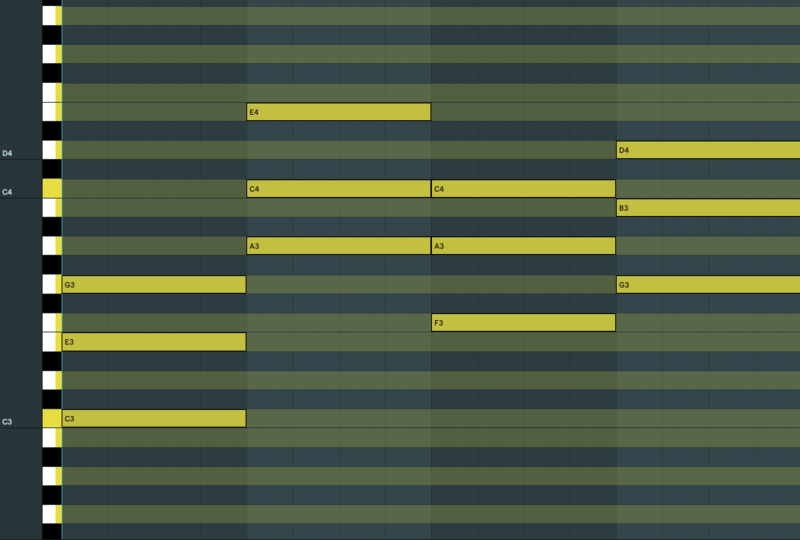

When we build triad chords – major and minor, for example – we take our notes from our current scale by starting on one, skipping one to another, then skipping one to another. If the scale is spelled 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, then our triad chord could be 1-3-5 or 4-6-1, for example.

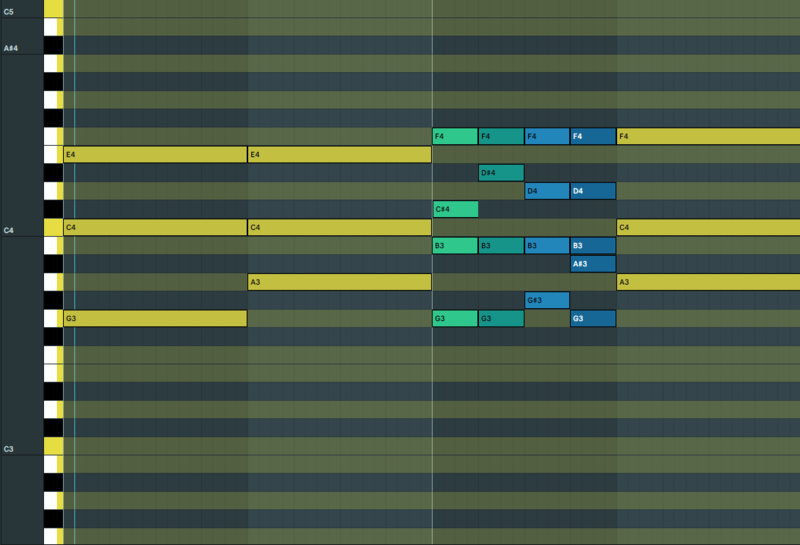

With extensions, we keep the pattern going, skipping another to get our fourth note, then skipping another to get our fifth. So those chords from before could go on to become 1-3-5-7 or 4-6-1-3-5. The image above shows the scale on the left, followed by two triads in the middle, and then some extended triads on the right.

2. Use inversions or ‘drop voicing’

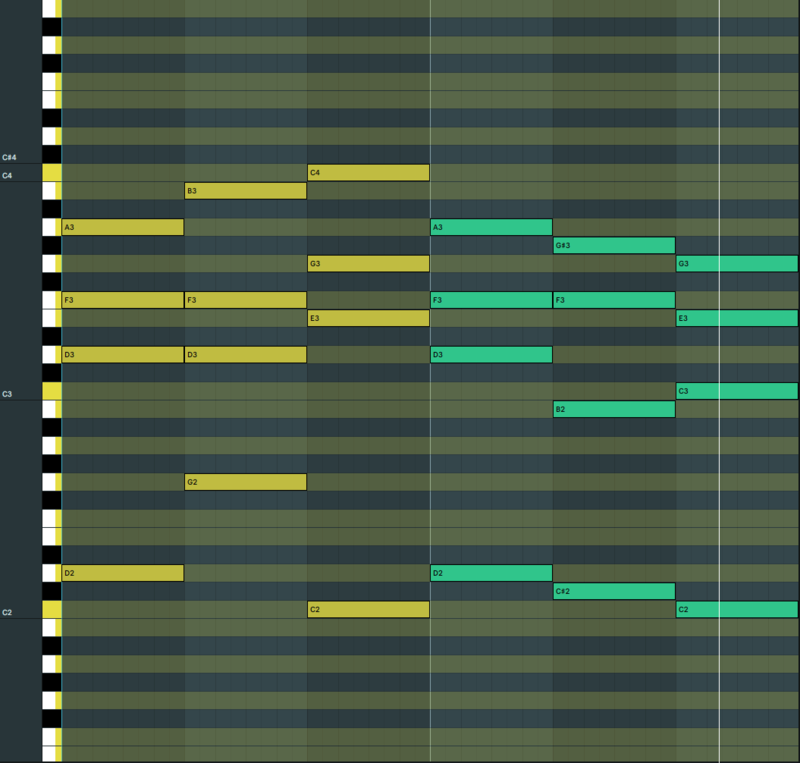

You may have heard of chord inversions before. The idea is that instead of having boring triads in the most basic “root position” – like C-E-G or B-D-F – you move a note or two from the top to rest below, or from the bottom to sit at the top – like G-C-E or D-F-B. The chords are still the same and serve the same musical function, they just have a more interesting twist. If you’re dealing with extended chords, as above, this is even more relevant.

A drop voicing is very similar, but has a particular context: this is taking a note from the top and inverting it to the bottom, but not the note previously at the top. So our C-E-G and B-D-F would become E-C-G and D-B-F. Drop voicing shows up more in extended chords, such as E-G-B-D-F turning into a B-E-G-D-F, for example.

You might apply a drop voicing to every chord of a progression, bringing the same note in each chord down an octave – moving the second from the top is called a Drop 2 Voicing, and moving the third from the top is called a Drop 3 Voicing. You can also choose to play those dropped notes with a different instrument, as they’re more like bass notes after being dropped down.

How do you choose which chord inversion to use for any given chord?

3. Try out voice leading for smoother movement

This tip finishes off a trilogy, which will be extra-useful if you’ve worked with the last two. Now that you have larger chords that are spread out, and you know how to invert them, how do you choose which chord inversion to use for any given chord?

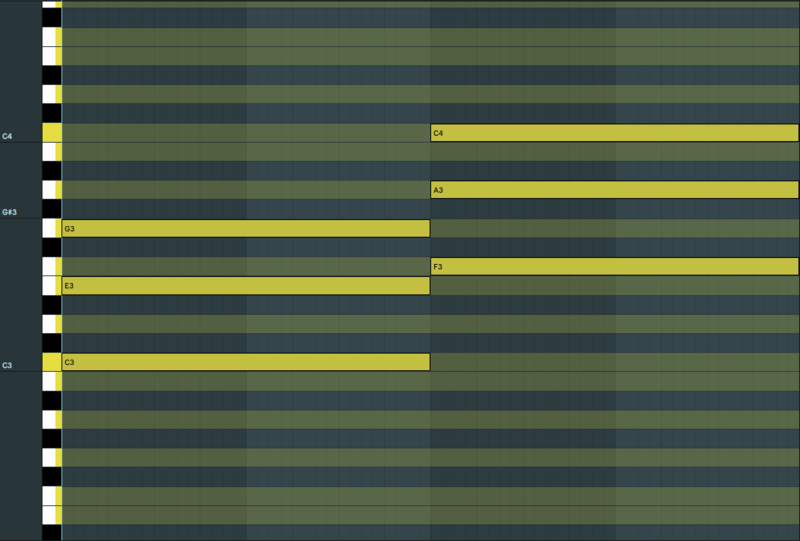

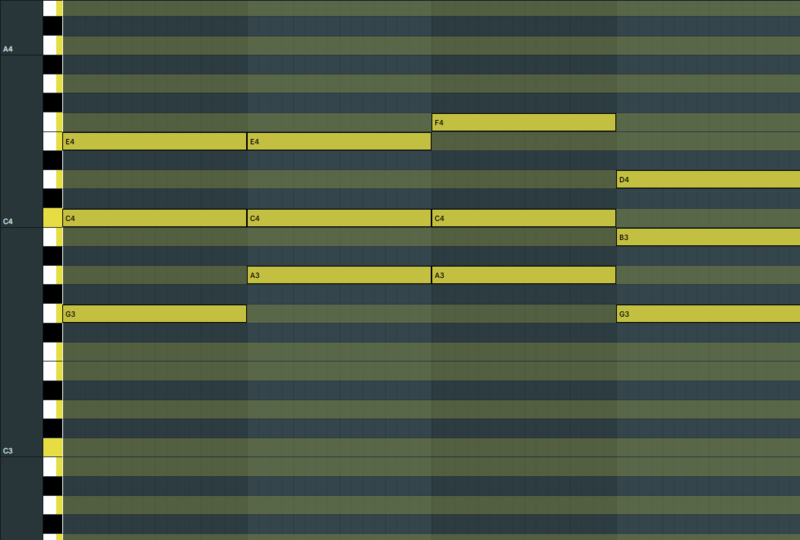

Start by looking at the following chord progression – just visually. You can see that the notes are all jumping between each other, and the instrument keeps moving up and down.

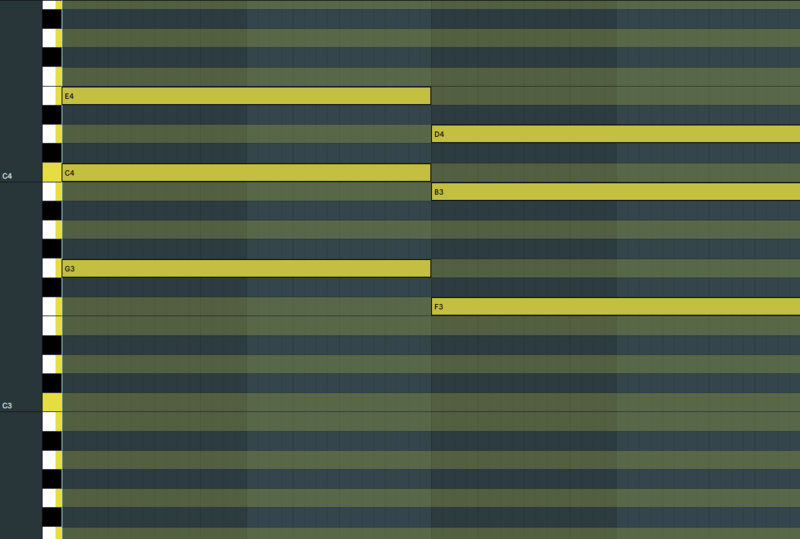

We can solve that with some voice leading. In essence, it means we choose inversions for these chords so that their notes flow together more smoothly. The reason for the name stems from when individual monophonic instruments play together to create a chord – each ‘voice’ should move as subtly as possible between notes, rather than notes. Here’s the ‘fixed’ version with better voice leading.

4. Chord substitution level 1: relative chord substitutes

Sometimes, we can simply swap one chord for another – that is, as long as we follow some rules on how to choose which one. We’ll show you three ways to do this over the rest of this article, starting with the simplest: relative chord substitution.

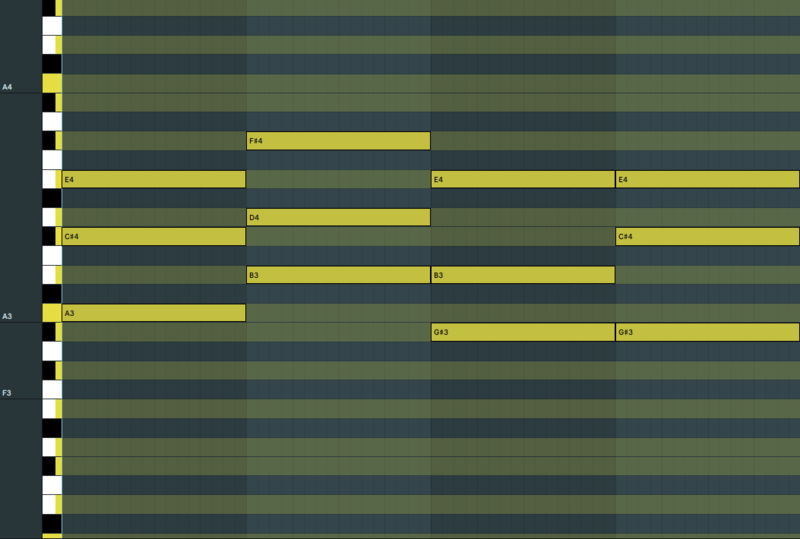

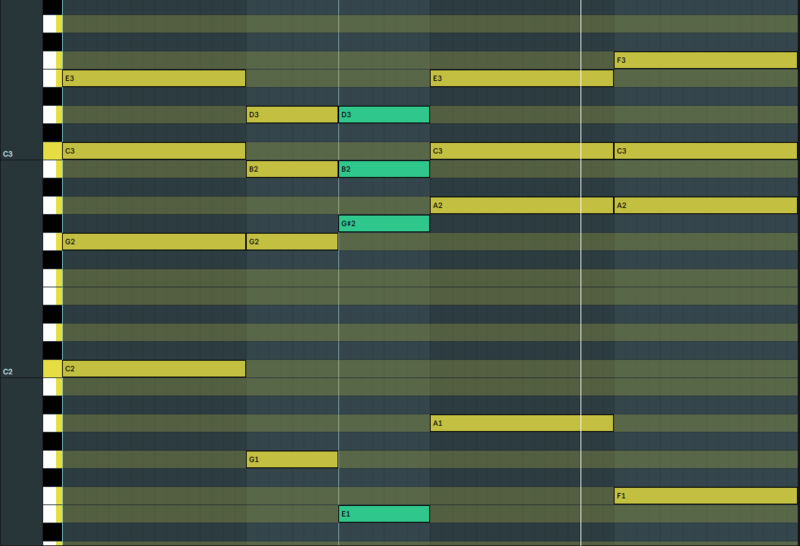

Here’s our basic progression, I–ii–V–iii progression, in A major, which uses the chords A major, B minor, E major, C# minor.

Let’s have a look at its second chord, B minor (B-D-F#). For reference, the scale notes for A major are A B C# D E F# G#. There are two chords in A major that share two notes with B minor: they are D major (D-F#-A) and (G-B-D). The practice of diatonic substitution means that these two chords can be swapped out for the B minor chord.

In the example above, we’ve also swapped out the E major chord for one of its diatonic substitutions: G#-B-D (G#dim).

One more thing: this kind of substitution will work especially well if there’s a melody on top of the chord that agrees more with the newly substituted chord (IE, it uses the chord’s notes at the same time).

5. Throw in an altered chord

If you have a dominant seventh chord in your progression (or can make one out of a dominant (V) in your progression, then there are some tried-and-tested substitute chords for that.

The fifth and the ninth are most commonly altered here, so if your C major progression contains the G7 chord (or you’ve used a secondary dominant, see below), you could alter it in the following ways:

Flatten the fifth (G7b5) to create dissonance, or sharpen the fifth (G7#5) for a complex, jazzy sound. Or, leaving the fifth alone, you could add a flattened ninth (G7b9) for a classical and jazz-style tinge, or sharpen the ninth (G7#9), also known as The Hendrix Chord, for a bluesy, cutting sound.

6. Chord substitution level 2: secondary dominants

These have a scary name, but the practice, while not a walk in the park, isn’t too frightening. A secondary dominant chord is created by temporarily pretending that the chord about to be played is a tonic note/chord, and playing its dominant seventh chord before resolving that to the original chord. Finished your word salad? Here’s a more edible example…

We have a progression C-G-A minor-F minor, and we want something a little spicy to happen before the A minor. Take the A minor and work out its dominant seventh: so work out the major chord a fifth up from it, and add a minor seventh to that (E7). The new chord is inserted before the A minor chord. See it in action below.

Secondary dominants work even better if the dominant seventh you choose fits in well with the previous chord of the progression. They can provide a very nice way to move between chords more smoothly, and can help in voice leading (see tip 3).

The secondary dominant will basically never fit perfectly in the scale you’re working in, but it’s still an acceptable adventure out into the unknown, and

7. Spread chords out further

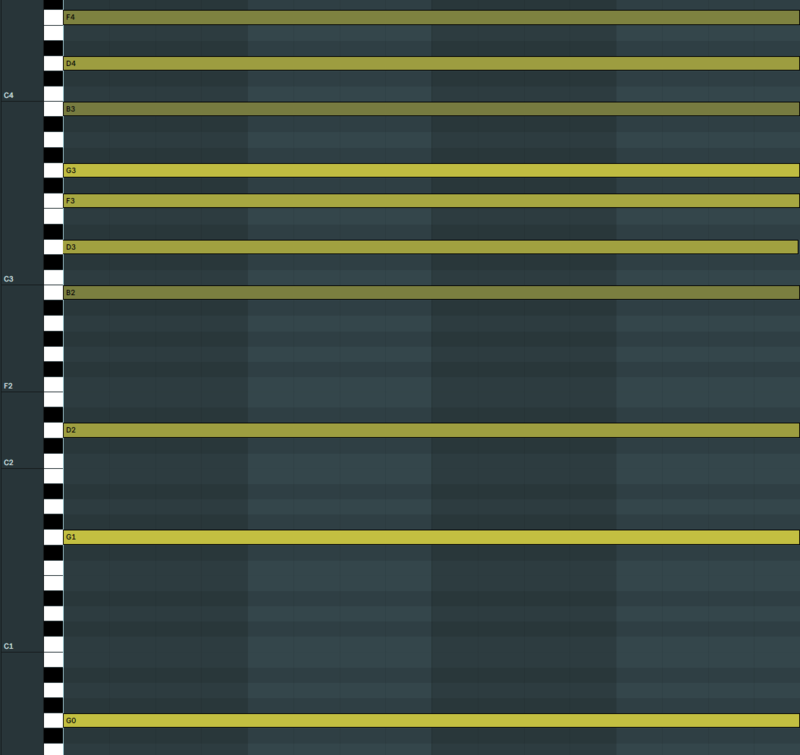

We've discussed using extensions, voicings and inversions in order to change which octave your notes are located in, but we can go even further with this. With electronic music, the possibilities for where to put a note are only limited by what notes you can actually hear. A normal inversion may extend a chord into two octaves, but what’s stopping you from playing a chord over, say, four octaves or even more?

To spread a chord out properly, without losing its effect, you’ll likely have to double up a few notes, repeating them in different octaves. It’s not a good idea to have a gap of octaves, as you’d risk the lower and upper notes of the chord being perceived separately.

You’d also have to make sure this move works in a production and mixing context: are you able to put other instruments alongside this wide chord? Will you need to use judicious EQ or a technique like multiband compression to make it work?

8. Chord substitution level 3: tritone substitution

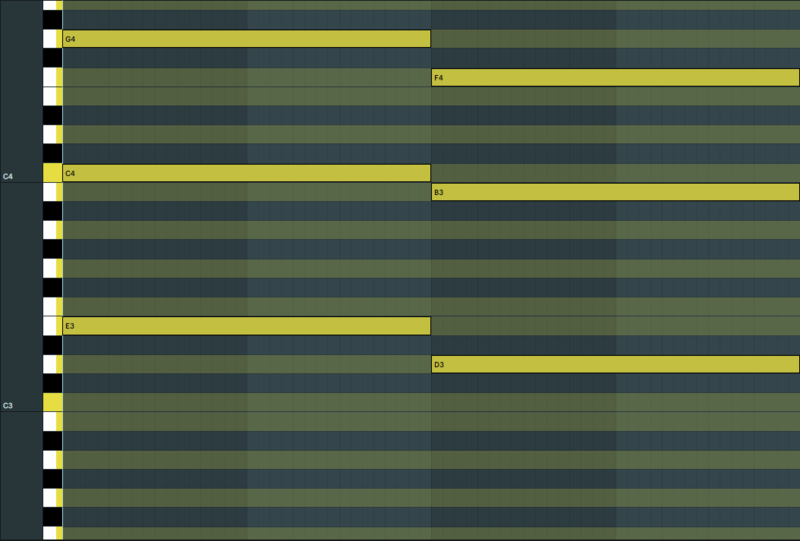

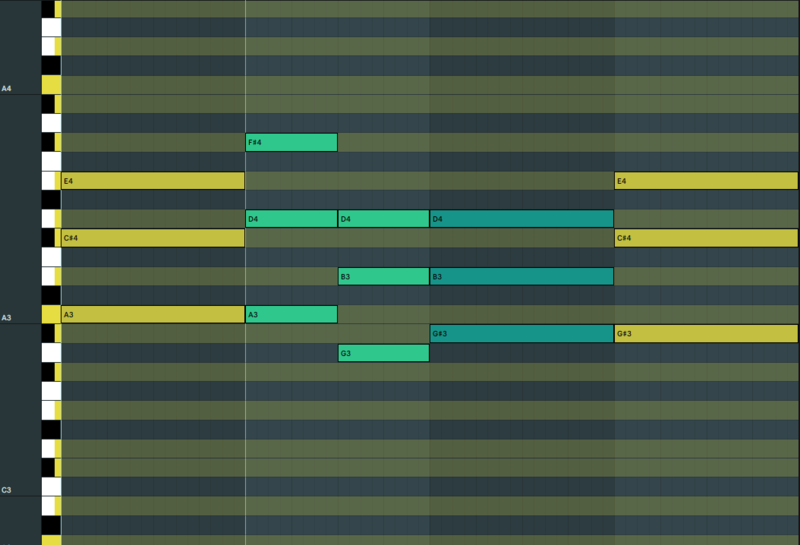

Our final idea should be simple if you’ve tried the previous substitutions, which rely on a dominant seventh chord being a member of the progression already. Here comes another one!

For a tritone substitution, take a dominant seventh chord, and literally shift it up or down by a tritone (AKA six semitones). The image below shows a very common ii-V-I progression (actually ii-V7-I) on the left, with the V7 swapped for its tritone substitution on the right.

Even if you don’t have a dominant seventh chord in your existing progression, if a dominant seventh would replace a dominant chord, then so would the same chord a tritone away!

FAQs

What is the difference between first inversion and second inversion?

A first inversion of a chord is when the bottom note, the root, is raised by an octave. A second inversion then takes the next lowest note, the 3rd, and raises this by an octave. For a C major chord that would look like: C-E-G (root position), E-G-C (1st inversion), G-E-C (2nd inversion).

When should you invert chords?

Chord inversions allow a composer the ability to flex their music around many situations. Some of the reasons you would invert chords are:

- Keep harmonic intervals closer together, masking harmonic change

- Extend out harmonic intervals of a chord

- Create variation without harmonic change

What are inversions for 7th chords?

As chords with a 7th in contain four notes, there are four possible inversions. These follow the same system as before: 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th inversions.

Are slash chords inversions?

A slash chord, such as C major/E does not refer to an inversion. Instead, the second note refers to what is played in the bass note, or left hand. For the example of C major/E, a C major triad would be played in the right hand with the E in the bass. This chord is a different harmonic function to a C major and has many uses.