Blog

How to Layer Sounds, Samples and Drums for your Best Sound Design Yet

25 Aug '2025

Far from just combining any samples with no intention, there’s a secret art to layering multiple samples and making sure they work together

When Aristotle said that “The whole is more than the sum of its parts”, we’re pretty sure he was talking about sound design and beatmaking. Perhaps he’d predicted Ableton Live and Serum 2, 2400 years before their time, or maybe he’d discovered an immutable truth that could apply in many situations as a generalised principle for understanding how things work. We’re not sure. But it certainly applies to music production!

Learning how to layer sounds properly makes you appreciate that ancient wisdom even more. A snare is an obvious example of layering sounds. Your chosen sample might have a good ‘crack’, but does it have the right ‘body’? If you can’t find the perfect sample in your collection, then using two is a way to make a unique, hybrid snare. But it doesn’t always go right.

To layer two sounds together and have it work, you either need good luck or real skill. There are principles behind layering sounds that we can use to help us fit them together like puzzle pieces. Employing these techniques will make you better at layering samples and help you create more unique music. In this article, we'll take you through it all.

Psychoacoustic sound design

A lot of this article uses techniques from Psychoacoustics, which is a science about how we perceive sound. The field makes observations about how we interpret and sometimes confuse sounds, and does experiments about how our perceptions can be changed and skewed, and therefore works out how our auditory perception works in general.

The principles that tell us how to layer sounds are based on psychoacoustic principles of “perceptual fusion” – the rules worked out for how two sounds fuse together in our minds.

Credit: Pawel Czerwinski

Have you ever been sitting in a room when two sounds happen at the exact same time? For example, an air condition comes on as a car starts up outside. Sometimes, if these two sounds happen perfectly in sync, we can get very confused as what we think is a new sonic event is happening, and our brains must try to work out what it is. Other times, the two sounds won’t fuse together in our perceptions, so we’ll continue to perceive them as two events, and hardly notice.

Psychoacoustics explains both of these possibilities, and helps us to use them in a music production context.

Timing two sounds to layer well together

In the example above, it was the sounds starting together – aka their “onset times” – that meant they were perceived to be a single sound. Let’s start applying this to music production.

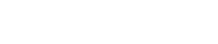

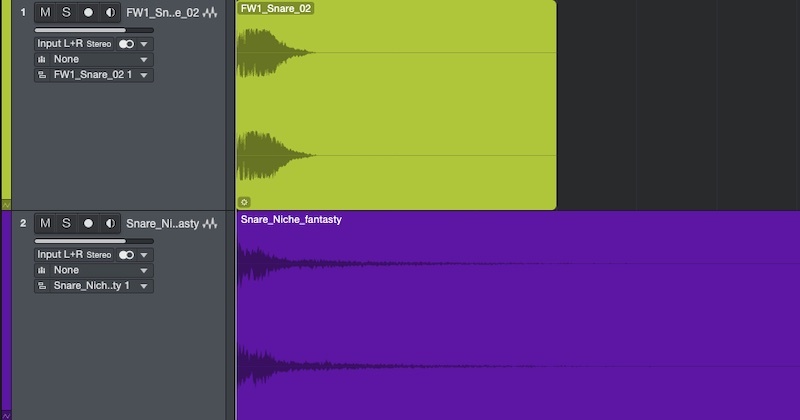

On Loopcloud, there are millions of sounds to browse and use. Let’s take a snare layer from EST’s Fourward Drum & Bass…

…and aim to combine it with a higher-frequency, clappier and reverbed layer from Niche Audio’s Tropical House Sessions.

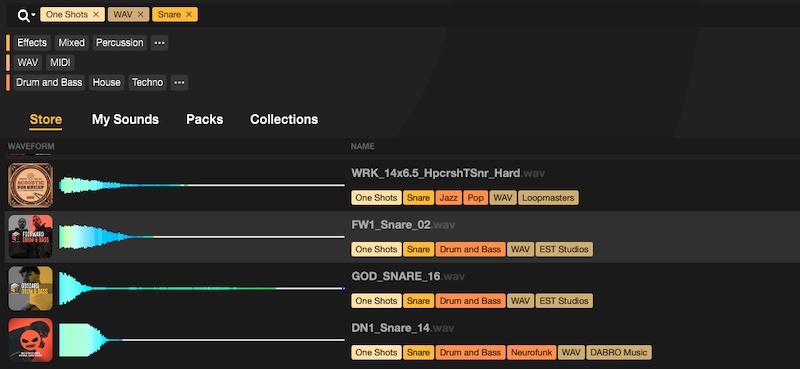

In our DAW, we can zoom right in and see how these two sounds might work together. One happens slightly after the other, and the second sound has a quick click and builds once again.

If we remove the initial click from the lower sound, and align the sounds so they start at the exact same time, as below, then you should work together, in theory.

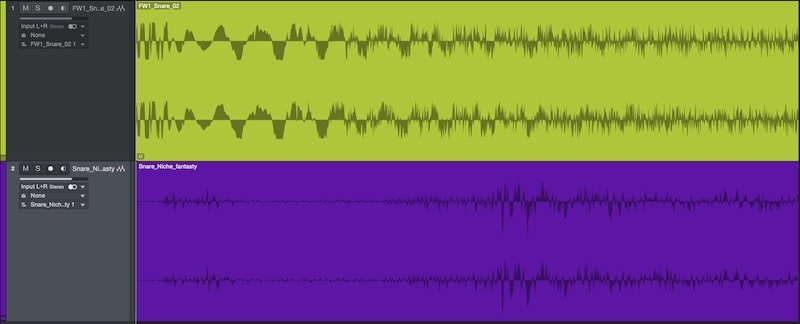

If the timing discrepancy is small, then it’s less hard to hear an improvement, but some sounds aren’t also quite trimmed right at their start, or take a short time to build. The amendment, as below, brings the two into line so they both crack in at the exact same moment, helping them to fuse together in our perceptions.

Offset timing

For short hits, it’s not always necessary to trim the endings of two sounds, but if your goal is to make them sound like one and the same sound, it can help. Our sounds here are very different in length as one layer has a very long reverb tail.

It’s possible to cut that long tail in the bottom sound. If we do so, we won’t get it ringing out after, and our listeners’ brains won’t get that extra perceptual cue to separate the two sounds out.

Tuning sounds to be more cohesive

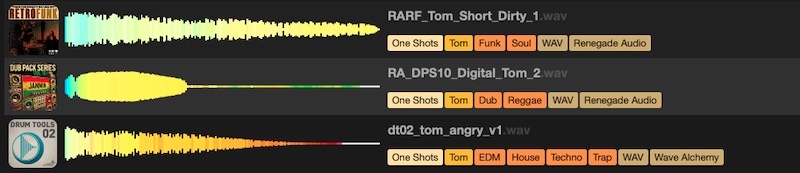

It might be slightly unconventional, but let’s now tune a bell sound to fit with a tom sound. The unconventionality works here, actually, as it will prove our point if we can use psychoacoustic layering principles to make these two sounds work.

If two sounds come from the same source, their harmonics are likely to line up and coincide. We can make that happen by retuning one of the samples.

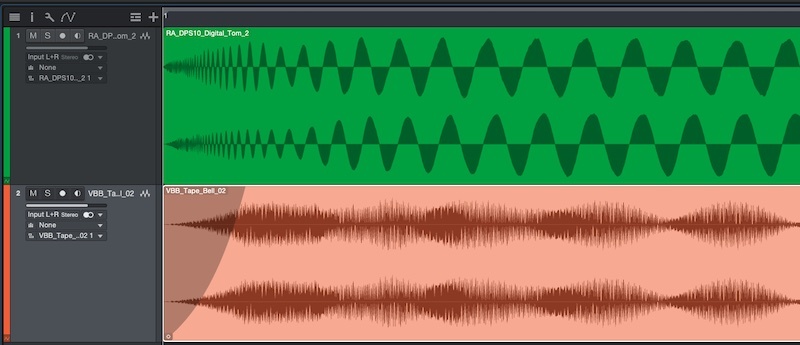

Our very disparate sounds are a digital synth tom sound from Dub Pack Series Vol. 10 - Jammin, and a clean but tape-infused bell sound from RV Samplepacks’ Vintage Beats & Breaks. They’re both one-shots, but it’s hard to find much more similarity than that. We’ll take care of that, though.

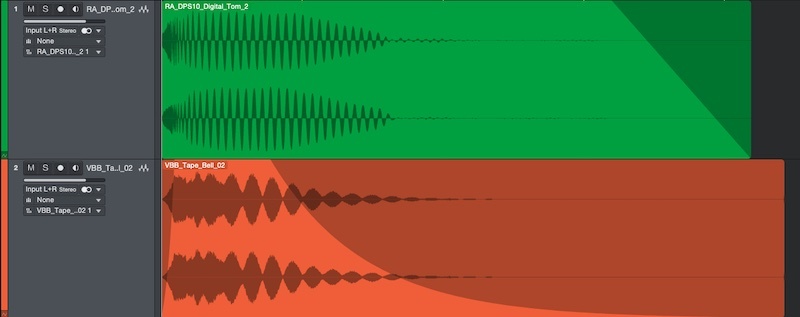

This time, we again take care of the two sounds’ onset and offset timing, making sure they start and end together.

Our next step is to tune the samples to fit together. Our bell has a very distinctive tone and a ‘note’ of its own, and it’s this sample that we’ll set about tuning. Believe it or not, the tom sound also has its own note.

We could get out a frequency analyzer or a note detector plugin, but actually, since the tom’s note can be hard to pin down, we can trust our ears more than these devices.

We then proceed by tuning the bell sound using our ears and our DAW’s sample tuning function, tuning it down until it sounds about right.

Panning and direction for layering

Psychoacoustics also teaches us that two sounds are more likely to be perceived as one if they come from the same direction.

In a music production context, this speaks to panning – ensuring that two channels in your mix are panned in the same place, and are therefore perceived to be coming from the same place.

It’s likely that if you’re layering two snare sounds, both will be panned centrally anyway, but this piece of knowledge could shed light on other good ideas: ensure any competing parts of the mix are moved away from each other, to help make them stand apart from each other.

Modulating sounds together

Another way to promote two sounds as seeming to come from the same place is in the modulation you apply to them.

Psychoacoustics has made it clear that if two sounds modulate together, they’ll be perceived as the same ‘thing’ in our brains. It’s easy to see why: there are lots of sounds coming from a passing car – four wheels and the engine – but as it moves past us (modulating all those sounds in the same way) we just think of that as “a car”.

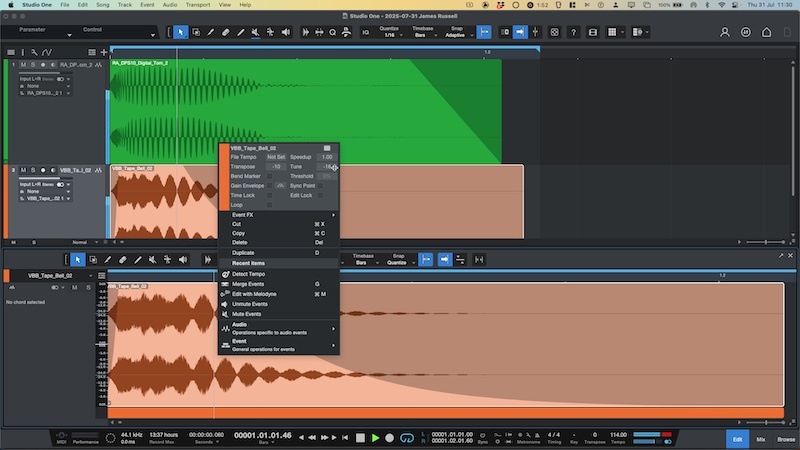

This doesn’t mean we should get an LFO and start waggling it in the same way over to disparate sound elements. Instead, it means that we should pay attention to the envelopes of our sounds. Do they start by raising from nothing to a high level? Do they tail off like an envelope’s ‘Decay’ section, or stay constant? How does their level drop, or change once it’s in a steady state? All these questions

In the image above, our two sounds have been made to rise in level in the same way. Our lower (orange) bell sound used to go from high to low, but now it rises more slowly. The next step would be to modulate the tom (green) sound to throb in the same way, if we wanted the two sounds to layer more cohesively.

Listening better

These layering techniques are grounded in theory and work well in practice. While they can direct you to how to solve problems in fitting sounds together, there’s no substitute for your ears in being the judge of whether it works or not.

Your choice of samples to layer together is still the biggest thing that will determine whether they work together, but these techniques can help you get out of a creative bind, and will help train your ears to understand what works and what doesn’t, making it easier for you to select samples that work well together in the future.